“It’s literally just clicking a button,” said Associate Dean of Student Life Joshua G. McIntosh.

Specially designed by Harvard University Information Technology, the lottery tool meddles only with gender ratio.

In each freshman class, the ratio of male and female students placed in any House cannot stray from the current gender balance in that House by more than 15 percent.

Once the simple mathematical algorithm spit out the housing assignments, the OSL checked the results to “be sure the lottery logic is performing correctly,” McIntosh said. It has never failed them so far, he noted.

Finally, the Housing Day letters were generated. The fateful pages waited, ready to be picked up by upperclassmen to deliver on Housing Day morning.

McIntosh said the OSL receives about one or two phone calls after each Housing Day from students or parents who are concerned about housing assignments.

ENTROPY

The housing assignment process has become increasingly less grounded in student choice since University President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Class of 1877, established Harvard’s residential House system in the 1930s.

Dean of Freshmen Thomas A. Dingman ’67 recalls that when he was an undergraduate, housing assignments were made through a competitive interview process in which House Masters selected interested freshmen.

Former Dean of the College Harry R. Lewis ’68 remembers of the House Masters’ selection logic, “If you had a string quartet that was part of the tradition of your House, you better make sure you have a cello.”

But in the 1970s, the policy changed. Students began ranking all the Houses in order of preference, taking the House Masters’ will out of the equation.

This shift came about as part of a “general movement toward student empowerment and student involvement,” Lewis said.

By the end of the decade, administrators modified the policy to limit students to ranking their top four Houses.

Under this revised system, students who received poor lottery numbers were sometimes unable to get into any of their top four choices and were instead randomly assigned to a House that still had vacancies—often in the Quad.

To avoid this fate, students sometimes sought to game the system by employing the strategy that Dingman remembers as the “Quad buster.”

Read more in News

Former Student Talks CartoonsRecommended Articles

-

Hoping for a New HomeThe competition for best House has always been a tumultuous one. Upperclassman housing at Harvard often means more than just ...

-

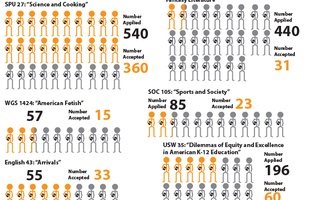

Lotteried Classes See Low Admission RatesIt is easier to gain early admission to Harvard College than get into a class with Harry Potter on the syllabus. While Harvard College admitted 18 percent of its early applicants in December, Professor Maria Tatar only admitted 10.5 percent of interested students to her class Folklore and Mythology 90i: “Fairy Tales and Fantasy Literature.”

-

Few Hit Jackpot In Course LotteriesAs the number of interested students in some already oversubscribed classes continues to grow and Pre-Term Planning data at times fails to accurately predict student interest, professors face the dilemma of how best to accommodate students while still maintaining the quality of their classes.

-

Senate Candidates Propose Differing Education PlatformsAs voters in the Commonwealth prepare to head to the polls on Tuesday to choose their parties’ nominees for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat, they will have to consider a number of education platforms ranging from consensus proposals to uniquely bold new ideas.

-

With Demand for Popular Courses High, Course Lotteries See Low Admissions Rates

With Demand for Popular Courses High, Course Lotteries See Low Admissions Rates -

The Love Song of An Awkward Prefrosh

The Love Song of An Awkward Prefrosh