After a head-to-head collision with Yale’s Jesse Reising in the 2010 playing of The Game, senior Gino Gordon laid on the ground for several minutes before standing up again, only to be put on a stretcher and taken to the hospital. Situations like these put the brain in serious danger.

All of a sudden, everything was black.

Chris Harvard lay on the rubber mat, unable to remember where he was and what he was doing.

Bubba had moved too fast, his kick had been about six inches closer than it should have been. And now, he was enveloped in pure darkness.

It is one of the few concussions former wrestler Chris Nowinski ’00 can even somewhat remember.

“I have memory of it partially,” the former wrestler says. “I don’t know what’s memory and what’s been recreated. It was amazingly not traumatic because no one [in the crowd] realized what really happened.”

But Nowinski knew the feeling. He had experienced it five times before.

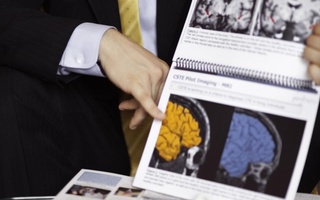

Nowinski’s time at Harvard and later his time spent as a professional wrestler would help shape what is now his life’s passion: ending America’s concussion crisis. As research increasingly shows that brain trauma has significant neurological implications—and can even induce severe depression—Nowinski has helped the public and professional athletes understand the serious risks posed by damaging blows to the head.

AN UNDERGRADUATE ATHLETE

The concussions began in college, back when Nowinski was a member of “The Polish Connection,” along with roommate Isaiah Kacyvenski ’00.

As best friends who share a Polish background, the pair anchored the heart of Harvard football’s defense for four years, including its 1997 Ivy League championship team.

“We ended up spending time as roommates,” Kacyvenski says. “I was the middle linebacker, and he was your nose tackle, so it worked...a lot of stuff we did we played off each other.”

Nowinski was a three-year letterman for the Crimson, achieving honorable mention All-Ivy distinction after his junior year and second team All-Ivy status following his senior season.

“He came to Harvard as a very good athlete,” Harvard coach Tim Murphy says. “Eventually, he became an outstanding player...he was one of the key kids on our ’97 championship team, just a kid you could always count on, a kid that was very dependable who was a great teammate to all the guys on the team.”

It was during his collegiate career that Nowinski received his first two concussions, but like many football players at the time, he did not report them to the coaching staff out of a lack of understanding of their severity and a desire not to appear weak. Instead, he chose to live with what he calls a “suck-it-up mentality,” one that still exists in college football today.

“With any injury, there’s a feeling of frustration that you can’t be out there with your teammates,” explains Harvard senior quarterback Andrew Hatch, who has suffered multiple concussions in the past.

Read more in Sports

TEAM OF THE YEAR RUNNER-UP: Crimson Dominates Nation’s BestRecommended Articles

-

Ivy League Leads Trend in Concussion PreventionThe winds of change howling through the world of sports safety have become impossible to ignore. Traditional football has nearly been toppled by the gusts, and the winds’ next victim, hockey, lies just around the corner. Adding to the drafts is none other than our little Ivy League. The breezes began back in 2009, when the NFL was called out by Congress for not adequately protecting its players from the dangers of concussions and other head injuries.

-

Who You Should Root for in the NFL PlayoffsHome team knocked out of the playoffs? Still reeling from Fitzpatrick’s fourth place AFC East finish? The Back Page has ...

-

Concussed: Down and Out

Concussed: Down and Out -

Panelists Discuss Head Trauma ResearchThree panelists described current medical research and long-term goals to reform care and policy on athletic head trauma and concussions during a biannual symposium of the Harvard Society for Mind, Brain, and Behavior in Science Center C on Friday afternoon.

-

Murphy Era of Harvard Football Turns 20Twenty years into his Harvard tenure, football coach Tim Murphy reflects on the most memorable games, seasons, and players of his career with the Crimson.

-

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab