“There were a lot of institutions that really didn’t want to care for these patients,” Groopman says.

In addition to the stigma attached to being gay, and uncertainty about the pathology of AIDS, Essex says that an early source of trepidation was the mystery of how the disease was transmitted.

“Not knowing at the time that it would be only sexually transmitted—as opposed to aerosol—generated a lot more fear [and enhanced] the discrimination that was then going on against the gay community,” Essex says.

According to Groopman, few in the medical community were willing to take a proactive stance in combatting AIDS.

“It required the personal commitment, both for laboratory scientists as well as clinicians including myself and Martin Hirsch, who said, ‘Yes, these are people who are very ill and suffering. We have limited treatments but we’re committed to helping them, and then we’re going to embark on a real effort to figure out what causes the disease and how to potentially limit it,’” Groopman says.

Multimedia

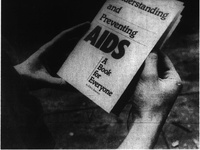

LOOK HOW FAR WE’VE COME

AIDS researchers and former Harvard students say there have been tremendous strides in both AIDS treatment and tempering the social stigma attached to the disease.

“The biggest difference between now and then is that AIDS was new ... and it was a death sentence. People who caught it died quickly,” Logansmith says.

Peter D. Gadol ’86, who helped organize an arts benefit for AIDS research as an undergraduate, adds that the current environment for gay and bisexual students is much more welcoming than the one that he encountered as a student.

“It’s not the same world. It’s interesting how, in many ways, the coming-out experience, which is very powerful to gay people, remains a vital moment,” he says. “There’s no doubt that the world is a different place than it was 25 years ago.”

However, according to Mermin, this is not a reason to underplay the consequences of the disease.

“There is almost a sense of complacency in the American public,” he says. “Twenty years ago there was more fear and stigma than the disease deserved, but now we have too few resources than are necessary to make a maximum difference.”

—Staff writer Barbara B. DePena can be reached at barbara.b.depena@college.harvard.edu. —Staff writer Brian A. Feldman can be reached at bfeldman@college.harvard.edu.