Although numerous suites in Mather House continue to share adjoining bathrooms, Lorelee S. Stewart ’86 recalls an instance in which the dorm room design was deemed unacceptable: a room of straight male students refused to use the same facilities as their gay neighbors for fear of being exposed to AIDS.

“We were at Harvard, where people are very smart and are some of the brightest students in the United States,” she says. “I was very surprised that this was how people were behaving.”

Such tensions played out at both the local and national level as AIDS began to dominate the media and arouse public concern. While Massachusetts Governor Michael S. Dukakis approved a policy effectively prohibiting gays and lesbians from acting as foster parents, the U.S. Surgeon General asked the public to engage in frank and open discussions about the disease.

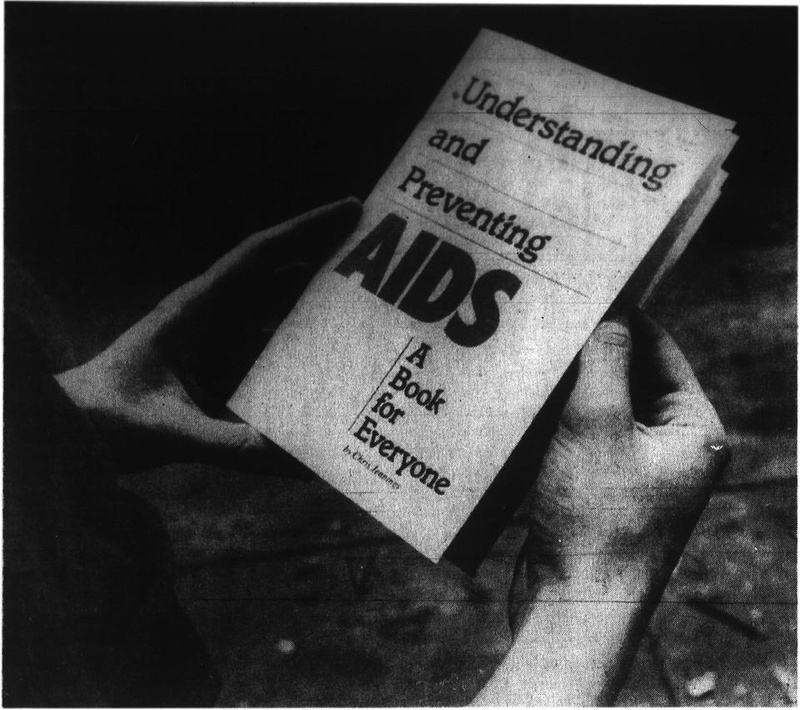

However, an incomplete understanding of AIDS transmission also polarized a fearful University and subjected both students and faculty to the consequences of stigmatization.

SUSPICION AND SICKNESS

Multimedia

According to Stewart, AIDS became a public health concern at a time when the societal climate was still hesitant to accept the sexual orientation of gay and lesbian students. Stewart, who was an open lesbian, served as a co-chair of the Gay and Lesbian Students Association, and recalls that the organization’s sign was torn down by another student during an event.

“That [episode] gives you an idea of what it was like to be out at that point in time,” Stewart says. “It wasn’t comfortable. It could be a complete nightmare.”

Christiana H. Logansmith ’87—a former member of the naval ROTC—says that while she stands by a letter she wrote to The Crimson in 1986 defending the military’s policy of excluding students with the AIDS virus, the conversations she overheard as an undergraduate suggested the pervasiveness of homophobia on campus.

“I remember hearing discussions between male students,” she says. “One of them, who was a fundamentalist Christian, was not happy about having a gay roommate. He had a walk-through and he didn’t like that because he wasn’t sure what he was exposing himself to as he came in and out of the room.”

Although a growing body of medical research indicated that AIDS could not be spread through casual contact, misconceptions about the disease remained widespread. Gay and lesbian students, in addition to those who showed an interest in AIDS research and advocacy, were targeted.

Jonathan H. Mermin ’87-’88 took a year off to participate in a research group analyzing the policy ramifications of the burgeoning disease. This work was met with skepticism by his peers, he says.

“I remember people asking me why I was working with HIV and having at least one roommate who was embarrassed about my research,” Mermin says. “There were still so many questions about whether AIDS was caused from an infectious agent or whether it was caused by something else.”

Mermin said that many people who were HIV positive were forced to deal with discrimination and stigmatization while also trying to cope with the realities of the disease.

“People were fearful about not knowing everything,” Stewart says. “A lot of people worried that [researchers] would discover something else about AIDS later on. No one wanted to take any chances.”

MEDICINE AND MISTREATMENT

Read more in News

Students Infuriated After Cue Guide Responses AlteredRecommended Articles

-

Lights Take HYPs; Heavies Persevere1996 Sports Statistics Record: Lights--3-0, 3-0 regatta; Heavies--3-3, 1-4 Lights Coach: Charlie Butt Heavies Coach: Harry Parker 1997 Consistency, consistency,

-

Centers in Africa Fight HIV/AIDSEarlier this year, Harvard’s two HIV/AIDS research centers in Africa each spun off limited liability companies, a strategic move that will open up funding streams that had previously been off-limits due to federal restrictions. For the 120,000 AIDS orphans living in Botswana, the potential funding increase could speed further advances in research as well as public health initiatives.

-

Ed School Screens Bullying Film

Ed School Screens Bullying Film -

‘Bully’ Targets Problem, but not Solution

‘Bully’ Targets Problem, but not Solution -

Curious George Reopens, Excited To Be BackCurious George Books & Toys, a once-popular specialty store located at 1 JFK Street, reopened last Wednesday under new ownership.

-

Square Personality: Adam S. Hirsch

Square Personality: Adam S. Hirsch