For the first time in its over 50-year history, the James Bryant Conant Prize is being awarded to a project consisting of wood, clay, twisted wire, and beams of light rather than a collection of words on a page.

Though the official results have not yet been announced, Quincy K. Bock ’11 was notified recently that her model of X-ray diffraction, designed to illuminate key elements of the famous Rosalind Franklin DNA image that contributed to James D. Watson and Francis H. C. Crick’s discovery of the double helix, will be one of the winners.

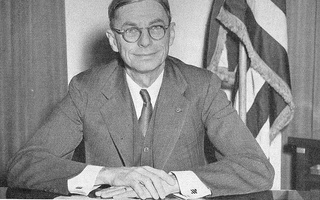

The prize was created in 1953 upon the retirement of Harvard University President Conant to reward students, especially non-scientists, for engaging science writing in interesting ways.

The prize was dormant for about the past 10 years, according to Administrative Director of the Program in General Education Stephanie H. Kenen.

Last year, with the initiation of the new General Education program, the prize was revived—but only this year was the submission criteria expanded to include artistic and multimedia projects in addition to papers.

Due to an increasing emphasis on creative assignments in Gen Ed courses, the committee thought it would be wise to welcome non-narrative submissions, according to Kenen.

“Students can use the same kinds of evidence and background as they might in an essay, but they’re doing it visually or in a spoken way,” Kenen said.

Bock, a Visual and Environmental Studies concentrator, coupled her interests in photography and science education to create a pedagogically useful piece of scientific artwork for the fall course Science of the Physical Universe 20: “What is Life? From Quarks to Consciousness.”

“We just vaguely touched on the discovery of DNA and this photograph in class,” said Bock, an inactive Crimson photo editor. “I thought it would be cool to figure out how it was taken and also analyzed because it’s very different from a regular photograph.”

Bock set out to create a projection box that imitated an X-ray diffraction machine like the one Franklin used. She also sought to show how Franklin’s 2-dimensional image depicts each 3-dimensional component of DNA.

Slides inserted into the projection box show the patterns created by different elements of a DNA double helix, including helices, phosphate groups, and base pairs. The project also features clay models of each 3-D structural element.

“What was particularly interesting about it was that she created this with a pedagogical idea in mind,” said SPU 20 professor Logan S. McCarty ’96, who is director of physical sciences education. “The hope was that students would simply put more of themselves into this and immerse themselves into the project more deeply than they would in a paper,” McCarty said.

But the projects have had an additional benefit, said physics professor Melissa E. B. Franklin, another SPU 20 instructor, who noted that the professors plan to use the model in future course lectures.

“If you look at the image, it takes about eight paragraphs to make it make sense,” Franklin said, explaining that words were not the best medium through which to teach about this photograph. “Just the way she pulls it apart would never have occurred to me.”

Bock, who has previously made other artistic science projects such as a wooden wave machine, said she appreciated having the ability to engage with science in a physical, creative capacity.

Read more in News

Students Consider University Recognition for Single-Sex GroupsRecommended Articles

-

Conant, Fischer, Counts Stress Learning Communist ConceptsPresident emeritus James Bryant Conant '14 opened the Summer School Conference on Teaching the Nature of Communism Monday night by

-

The Lamont Education

The Lamont Education -

'Against the Root of Privilege'

'Against the Root of Privilege' -

Harvard and the Fabric of a Nation

Harvard and the Fabric of a Nation -

Past Tense: Finding a Place

Past Tense: Finding a Place -

Undergraduates "Surrender to Raw, Mass Impulse"

Undergraduates "Surrender to Raw, Mass Impulse"