This is not a prescription for a "trade school." There is nothing low-class about professional competence. It is a pre-requisite for leadership and innovation.

2. Professionals being educated at the GSD must be conversant with the latest concepts being used in their profession.

We are not advocating slavish imitation of one established procedure or another, only pointing out that, if the student professional is not fully conversant with the best of current thinking, he will not make the best use of his education. Re-inventing the wheel, unless consciously used as an educational device, is unlikely to be the best use of the student's time.

3. Professionals being educated at the GSD need to become conversant with a number of different disciplines.

Urban and environmental problems require interdisciplinary solutions. One reason that we believe that Harvard's Graduate School of Design can and should become pre-eminent is the strength of Harvard as an institution. We are astonished at how little the separate departments and programs at the GSD benefit from each other, or from their position in a great university. The Committee is conversant with the "separate bottom" description of Harvard's finances, but believes that it is perfectly possible to devise a workable system of co-operation between different elements of the University.

ARCHITECTURE

The Committee recognizes that the problems we discern in the Architecture Department are common to many schools of architecture and arise from a single central difficulty: the need to develop both the student's technical competence and his creative abilities. Too much technique may stultify a student's imagination, too much specialized design investigation leaves the student without the ability to translate ideas into buildings.

At the time of our visit in May, 1975, the visible symptom of an underlying malaise in the Department of Architecture was a surface placidity: the belief, as one faculty member explained it, that the heroic period of innovation is over in architectural design, and all the student can be expected to do is to master what has already been done. One student said: "The faculty is bored with us, and we are bored with them." In April, 1976, most of the discussion centered around what the Dean did, or did not say, before, during and after a speech in Seattle.

We do not agree that there is no more need for innovation in architectural design; theory and practice are probably changing faster now than they ever have before. We agree with the Dean's statement, in his famous Seattle speech, that architects have defined their role in American society too narrowly. Before an aspiring architect undertakes an expanded role, however, he must first learn to be an architect.

Our suggested change in policy for the Department of Architecture would be to give much more direction in technical matters, and permit much more freedom and diversity in matters of design.

The composition of the faculty inevitably gives too much emphasis to the tenets of "modernism" as formulated in Europe 50 years ago. The Department needs an infusion of talented new faculty who will advocate other points of view. We emphasize that faculty in the Architecture Department must maintain a continuing relationship with architectural practice if they are to continue to be effective teachers. The School should beware of personnel policies that prevent successful practitioners from teaching.

The Department should also give priority to re-evaluating its "core" curriculum. It is not possible for the Committee to make a definitive judgment about it on the basis of our visits, but we strongly suspect, based on the student work that we have seen, that the student is not becoming sufficiently proficient in the basic techniques of architecture at an early enough point in his education.

If the architect is indeed to widen his role, as the Dean has suggested, the architectural student must become familiar with the context in which this wider role is played. He must understand more about business, particularly real-estate, about law and government, about politics and society. At the same time, students in these other areas need to know more about architecture, or they will not appreciate what an architect might be able to do to help them. "Separate bottoms" or no separate bottoms, we believe that it is possible to work out reciprocal courses: architecture for business students, business for architecture students. We appreciate the difficulties: the environmental or architectural material offered to law or business students must be part of the main curriculum, otherwise highly competitive law and business students won't take the courses. We believe it essential, however, that reciprocity be established, for the mutual benefit of each professional school, even if it requires intervention at the highest administrative level. Following the line of least resistance and allowing a book-keeping device to set educational policy would be to deprive Harvard of one of the major benefits of being a great university: the creative interaction of its different components.

URBAN DESIGN

If the architect is to widen his professional role, a major way of doing so is through urban design. Harvard was one of the first institutions to recognize urban design as a separate curriculum. We are surprised to find, therefore, that urban design at the GSD is apparently regarded as something of a "step child," and that its continued existence as a separate program is in question. Surely, if there is a "growth area" in architecture today it is urban design, which is attaining increasing significance in the planning and landscape architecture professions as well.

Read more in Opinion

Justice for the PalestiniansRecommended Articles

-

Design Faculty Votes To Increase Admissions From Minority GroupsThe faculty of the Graduate School of Design has approved measures to intensify recruitment of qualified students and professors from

-

Interim Design Dean Will Remain in PostUniversity President Lawrence H. Summers announced Wednesday that Alan A. Altshuler, who was elected interim dean of the Graduate School

-

Architects, Urban Planners Address Racial Tensions in St. LouisThe Graduate School of Design kicked off a three-day event with keynote speeches that focused on racial justice in St. Louis, Mo., a continuation of a series addressing design, space, and social justice at the school.

-

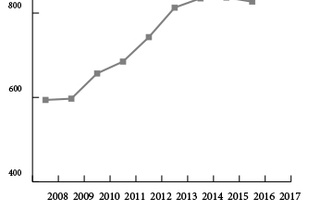

Graduate School of Design's Enrollment Soars Skyward

Graduate School of Design's Enrollment Soars Skyward -

Obama to Appoint Two Design Professors to Federal CommissionPresident Barack Obama intends to appoint Graduate School of Design professors Toni L. Griffin and Alex Krieger to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts.