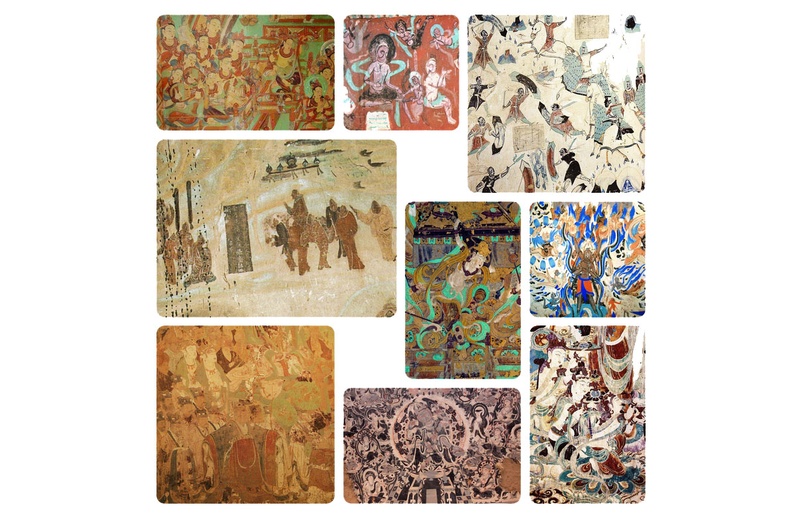

It was 1924, and the art historian Langdon Warner was face to face with a work of breathtaking proportions. The adventurer who would later help inspire Indiana Jones couldn't take his eyes off of the Tang dynasty murals painted upon the walls of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, China. They were so dazzling that “there was nothing to do but to gasp,” he later wrote in his book “The Long Old Road in China.”

But Warner would do more than just admire the painted caves. After making the appropriate arrangements to remove some of the murals in an effort to preserve them, he used a special chemical solution to peel the frescoes from the cave walls. But to his horror, the solution froze before the removal process was complete, damaging the frescoes and leaving marks on the site itself.

With a dozen murals in tow, Warner returned to Cambridge, Mass., where he had graduated from Harvard College in 1903 and now taught Chinese art. Today, nearly 90 years later, the murals remain in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums, and until the closure of the Fogg in 2008 for renovation, they had never been taken off exhibition to the public.

But back in China, Warner's acquistion caused outrage. The murals he removed are still considered stolen goods in China, and Warner is viewed by some as a thief—plaques in the museum at Dunhuang even designate him as such.

Warner's acquisitions raise questions about the way prominent museums currently acquire, hold, and display art. These questions are no less relevant for Harvard's museums, whose collections contain pieces from across the globe and throughout history. Such diverse holdings make it necessary to ethically determine who has custody over works of art and negotiate the point at which an item transcends being a piece of art and becomes an exploited piece of culture.

Custody Battle

Although the murals have temporarily removed from display, there is no plan to send the wall paintings back to Dunhuang any time soon despite the controversy surrounding them, according to Melissa A. Moy, associate curator of Chinese art at the Harvard Art Museums.

Moy says the issue is much more complicated than some make it out to be. “It [was] such a different time, and it's hard to look back at it really with a 21st-century lens and really have that full understanding of everything,” Moy says. “I can say in my years here there have been one or two letters that we have received from people who visited Dunhuang who are outraged by the fact that Harvard has these things and are demanding them back. But all we can do is try to explain the circumstances and explain that Dunhuang themselves have not asked for it back.”

The fact that Dunhuang museum officials have not requested the return of these murals even further complicates the argument that they should be returned. “If there is a legitimately contested object that one could prove was stolen, then of course we would proceed in taking the steps to return it to its rightful owner,” Moy says. However, she does not believe this to be the case with the Dunhuang murals.

“I tend to want to think of it like, ‘Well, there were good intentions,’” she says. “[Warner] went about asking for permission. He actually paid for some of these things… and it was sort of accepted at that time because there wasn't a national widespread appreciation for the caves yet. And he was seeing a lot of natural damage and man-made damage that was happening.” Now that they are at Harvard Art Museums, Moy says, these pieces are well protected and preserved.

However, while these murals were technically bought, the Chinese view the purchase in a much harsher light. Daniel N. T. Yue '16, a Crimson design executive, got a view very different from Moy's during his 2013 trip to China. “[In Dunhuang] there's not much debate. It's pretty clear that it's theft to them and that [the mural] should be returned,” Yue says.

Moy understands the some of such outrage. “I think what makes it hard is that one can see the obvious scars of the work he did [in Dunhuang].” Stark white gaps in the colorful Dunhuang wall paintings serve as a continued reminder of Warner's removals, which some view as an example of looting by imperialist powers.

Though Moy does not condone Warner's methods for removal, she believes that the purpose of his mission has been unfairly demonized, regardless of the damage it caused. “It was really an effort to try and promote the study of a very glorious art tradition that wasn't well understood yet,” she says. “It was kind of ironically a preservation act.”

Legal Frameworks

In an attempt to prevent further controversies like the one surrounding the Tang Dynasty murals, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) met in 1970 in Paris. Their mission was to discuss the “the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural and educational purposes increases the knowledge of the civilization of Man,” according to UNESCO's official website. At this conference, UNESCO enacted the laws by which international museums must currently abide. On the Harvard Art Museums' collecting policy page, the guidelines state that the museum will not acquire any piece that may have been illegally taken after Nov. 17, 1970, in accordance with the UNESCO agreement.

Read more in Arts

"Daisies" Exhibit Takes Playtime Seriously at GSERecommended Articles

-

Lowell House Art Project to Brighten Walls

Lowell House Art Project to Brighten Walls -

Hip Not Hipster: McSweeney’s Editors Deliver a Funny TalkTwo McSweeney’s editors share comic stories from their careers.

-

Panel Talks Bipartisan Economic Policy

Panel Talks Bipartisan Economic Policy -

Failure in the Face of TragedyWe do not understand how they could look into the faces of gun violence victims and their family members and vote the way they did. They will have to answer for their actions. We await the day with dread.

-

Men's Hockey Nabs Second ECAC Win

Men's Hockey Nabs Second ECAC Win -

Eagles Travel to Cambridge in Crosstown ShowdownOn Wednesday evening, former Bruin and NHL legend Bobby Orr will be in Cambridge to sign copies of his achievement-filled autobiography. Merely a short walk across the river on that same night, the Harvard men’s ice hockey team and the Boston College Eagles will vie for achievements of their own in the crosstown matchup.