The University balances higher expenses with reduced budgets in the long wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The 2008-09 academic year kicked off in the midst of exceptional growth: The campus had expanded with the successful construction of Northwest Laboratories only a year before, and school budgets were quickly growing to accommodate more faculty.

But just a few weeks after students returned to campus from their summer vacations, the American markets crashed. And as stock prices slipped, so did Harvard’s endowment. Between the University’s direct holdings of financial securities and assets managed by external financial institutions, the endowment dropped by nearly 30 percent, tumbling from $36.9 billion down to $26 billion.

Fast forward to today. The University is approaching the end of its 2012 fiscal year. Saddled with reduced income from a still-depressed endowment, the University is currently managing increased budget responsibilities while wading through the continued ripples of the financial crisis that struck nearly four years ago.

“We have a smaller endowment and larger obligations,” University President Drew G. Faust said. “Those are very real challenges for us.”

A TEAR IN THE HULL

As Harvard’s endowment posted losses of nearly 30 percent in late 2008 and early 2009, deans and department administrators scrambled to cut budgets. Across the University, 275 workers were laid off, and hundreds were given reduced work hours. According to Wayne M. Langley, higher education director for Service Employees International Union Local 615, which represents many service employees at Harvard and other institutions in New England, unionized service workers at the University lost on average five hours of work per week.

“That may not seem like a lot,” said Langley. “But for people who are low-income workers, that makes a big difference.”

Harvard was trying to trim as much as it could. In order to pay for their budgets, schools in the University collect incomes from the endowment, annual donations, federal funding, and student tuitions. Normally, this revenue covers the total expenses of each of the schools.

But 2008 was not a normal year. As the University’s endowment tanked, donations, net tuitions, and other sources of incomes slowed to a drip, too. But by the time the market collapsed, the Harvard Corporation, the highest governing body of the University, had already approved the University’s budget through June 2009.

Pressed by reduced income to pay for their annual expenses, schools cut budgets to varying degrees.

BAILING THE WATER OUT

Starting in the winter of 2008-09, the Business School turned down the thermostat a few degrees at night to save at the margins. Administrators encouraged community members to shut down their computers at the end of the day and installed new, energy-efficient windows. But even as the financial outlook for the University has improved, the Business School has not gone back to its old habits.

“We thought to ourselves at the end of the recession, ‘Do we keep this in place?’” Business School Chief Financial Officer Richard P. Melnick said.

Administrators have appreciated the new challenge of paring their respective budgets, enjoying the new efficiency the focus has granted the departments. Most of these tune-ups are here to stay, even as the University recoups its endowment’s value and respective distribution increases.

“All of those kinds of scrutiny and efficiencies that came out of questions we asked in the wake of the downturn—we will continue,” Faust said.

Read more in News

The Cooperative CouncilRecommended Articles

-

Housing Budget Cuts ContinueWhile administrators and tutors can speak at length about how the limited effects of the cuts, no one is certain as to when they will end—and given history and future plans, that end may not come anytime soon.

-

Following Evaluation, House Budgets See IncreasesHouse budgets have been modestly increased by five percent or less this year—with Quad House budgets increasing the most—due to an extensive evaluation of House finances initiated in the midst of the financial crisis.

-

FAS Hopes For Increased Endowment FundingSenior administrators in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences have provided loose guidelines to departments for long-term financial planning that foresee a growth in the distribution from the University endowment to pre-2008 nominal levels by 2018.

-

Professors Share Views on Election Win for ObamaOn Wednesday, several Harvard professors said that while they reacted to Obama’s victory Tuesday with a level of enthusiasm similar to that in 2008, his win in 2012 was momentous for different reasons.

-

Triangulate or DieNo party can establish for itself a viable future if that future hinges on low turnout among young people and minorities. It is not only morally wrong, but also futile.

-

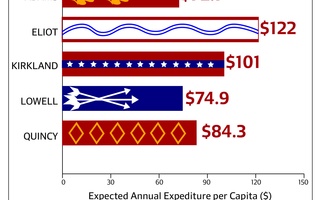

Analysis Reveals Disparity in House Committee Budgets

Analysis Reveals Disparity in House Committee Budgets